I. Introduction: Education as a Cornerstone of American Prosperity

Education in the United States is a fundamental driver of individual opportunity, national innovation, and societal well-being. A well-educated workforce is crucial for sustained economic growth, technological advancement, and global competitiveness. Federally funded research and development (R&D) at world-class universities, for instance, has been instrumental in creating countless technologies, from the internet to breakthrough medicines, directly contributing to economic prosperity. Increases in educational attainment have been responsible for an estimated 11% to 20% of worker productivity growth in recent decades.

The American education system is a vast and decentralized enterprise, primarily funded through a blend of local, state, and federal sources. This multi-layered approach, while allowing for local control, also leads to significant variations in funding levels and distribution, impacting accessibility, equity, and educational outcomes.

II. K-12 Education: Funding Structures and Inherent Disparities

Public K-12 education in the United States is financed through a complex tripartite model involving federal, state, and local governments. In fiscal year 2023, total spending for public K-12 education reached $947 billion.

A. The Tripartite Funding Model

The majority of K-12 funding originates from state and local governments, which collectively provide about 87% of all school funding.

Table 1: K-12 Education Funding Sources by Share (FY 2023)

| Source | Share of Total Funding (%) |

| State | 45% |

| Local | 43% |

| Federal | 13% |

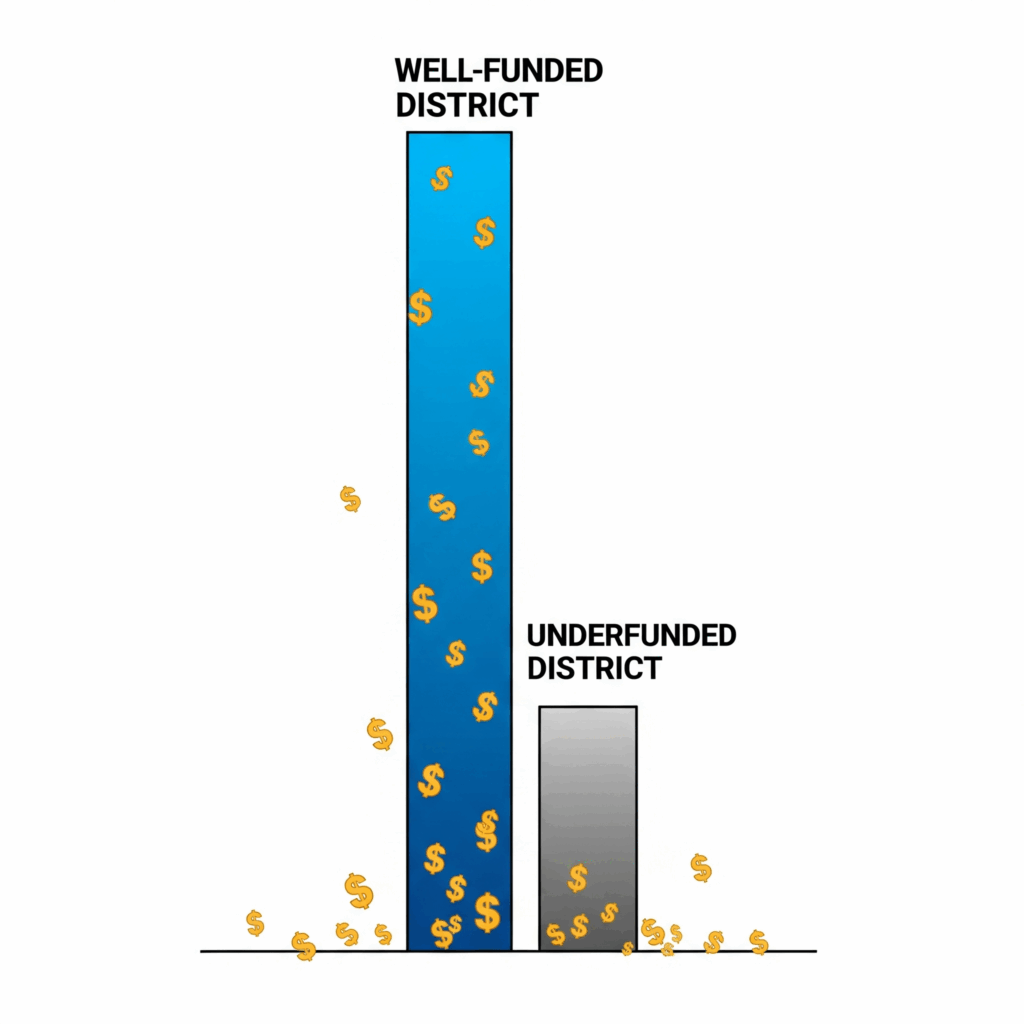

- Local Contributions: Primarily derived from property taxes, local governments contribute approximately 43% of K-12 funding. This reliance on local property wealth means funding can vary widely based on property values and tax rates within a district. This system is deeply rooted in historical policies like “redlining,” which created unequal tax bases and perpetuated disparities, particularly for communities of color.

- State Funding: State governments provide the largest share, about 45%, typically from sales and income taxes. States use complex formulas to distribute funds, aiming to bridge gaps between local revenue and a minimum funding level. However, these formulas often fall short of achieving true equity, with many states still allocating less funding to high-poverty districts or those serving more students of color.

- Federal Contributions: The federal government contributes a smaller but vital 13% of K-12 funding, primarily through specific grant programs like Title I (for low-income students) and IDEA (for students with disabilities). While intended to narrow funding gaps, federal contributions are often insufficient to significantly improve overall funding in states, and their impact can be limited by how states distribute these funds.

B. Challenges to Equitable K-12 Funding

The multi-layered funding structure, coupled with historical inequities, presents significant challenges:

- Impact of Economic Recessions: Economic downturns severely impact K-12 funding. The Great Recession (2007-2009) led to deep cuts in state and local education budgets, with many states failing to reinvest adequately even as their economies recovered. This resulted in public schools collectively losing nearly $600 billion in state and local revenue between 2008 and 2018, creating a “lost decade” of state disinvestment.

- Wealth and Racial Disparities: The reliance on local property taxes creates persistent funding disparities. High-poverty districts receive about $1,000 less per student than wealthier ones, and districts serving more students of color receive $1,800 to $2,700 less per student than those with fewer students of color, even when controlling for income.

- Consequences of Underfunding: Inadequate funding leads to fewer resources, less qualified teachers, and poorer curriculum offerings in disadvantaged schools. This directly contributes to widening achievement gaps, higher dropout rates, and reduced college-going rates, with long-term economic and social costs, including higher unemployment and increased reliance on public assistance.

III. Higher Education: Navigating Diverse Revenue Streams and Rising Costs

The financial landscape of higher education in the U.S. is characterized by diverse revenue streams, rapidly escalating costs, and a complex array of financial aid mechanisms.

A. Funding Landscape and Federal Role

Institutions of higher education (IHEs) draw funding from federal, state, and local governments, student tuition, endowments, and other sources.

- Public Institutions: These are supported by state and local government appropriations, alongside student tuition and fees. State funding is typically the largest source for community colleges, while four-year universities rely more on tuition and sales/services (e.g., university hospitals).

- Private Institutions: Primarily funded through tuition, donations, and endowments. Endowments, built from charitable contributions, provide investment income to support institutional missions, though a 1.4% federal excise tax was introduced on large endowments in 2017.

- Federal Government’s Role: The federal government’s primary emphasis in higher education funding is student aid, distributed through grants (like Pell Grants) and loans, rather than direct institutional support. Federal R&D funding also significantly supports university research.

B. The Escalating Cost of College

The cost of higher education has dramatically increased, far outpacing inflation and wage growth. Tuition alone nearly tripled between 1963 and 2022 (inflation-adjusted).

Table 2: Historical College Tuition Inflation Rates by Decade (Public 4-Year Undergraduate)

| Decade | Average Annual Tuition Inflation Rate (%) |

| 1980s | 9.23% |

| 1990s | 6.58% |

| 2000s | 7.51% |

| 2010s | 3.05% |

Key factors contributing to this escalation include:

- State Funding Cuts: Significant reductions in state appropriations, especially after recessions, have forced public institutions to raise tuition to cover revenue gaps.

- Administrative Bloat: Colleges are spending more on non-teaching administrative staff, contributing to rising payrolls and tuition.

- Amenities Arms Race: Competition for students leads universities to invest heavily in non-academic amenities and services, driving up costs passed on to students.

- “Bennett Hypothesis”: This theory suggests that the availability of federal student aid allows colleges to set higher tuition rates, knowing students can cover the cost through grants and loans, reducing market pressure to keep prices low.

IV. The Student Loan Debt Crisis and its Economic Ramifications

The accumulation of student loan debt has become a pervasive financial challenge, representing the second-highest consumer debt category after mortgages.

A. Scale of Student Debt and Economic Impact

As of 2024 Q4, student loan debt in the U.S. totals $1.777 trillion, with federal loans accounting for 92.2% of this total. The average federal student loan debt balance is $38,375.

This debt has significant economic ripple effects:

- Delayed Homeownership: Student loan debt is a major obstacle to purchasing a home, delaying it by an average of four months for every $1,000 increase in debt for young graduates.

- Reduced Consumer Spending: Debt directly reduces consumer spending, with a 1 percentage point increase in debt-to-income ratio associated with a 3.7 percentage point decline in consumption.

- Inhibited Entrepreneurship: Aspiring entrepreneurs are 11% less likely to start a new business if they carry more than $30,000 in student loan debt.

- Systemic Risk: The sheer scale of student debt and high delinquency rates (4.86% for federal loans in 2024 Q4 ) pose a systemic risk, potentially leading to a “recession in slow motion” if mass defaults occur, impacting credit scores, employment, and government revenue.

B. Financial Aid Effectiveness and Limitations

While financial aid aims to make college accessible, its effectiveness is constrained:

- Declining Pell Grant Purchasing Power: The maximum Pell Grant, once covering over 75% of a four-year public college’s cost in 1975-76, now covers only about one-third. This erosion disproportionately affects low-income students and students of color, forcing greater reliance on loans.

- Unmet Need and Complexity: Many students, even with aid, face significant “unmet need”—the gap between costs and aid. The complex FAFSA process also means billions in eligible Pell Grants go unclaimed annually.

- Federal Tax Policy Impacts: Education tax credits and deductions offer some relief , but recent changes, like the elimination of federal Graduate PLUS loans and caps on Parent PLUS loans, could push students toward higher-interest private loans.

V. Policy Considerations and Recommendations

Addressing the multifaceted fiscal challenges in U.S. education requires comprehensive and strategic reforms:

- Enhancing K-12 Funding Equity and Adequacy: States must adopt and fully fund equitable formulas that provide additional resources for students with greater needs, moving away from over-reliance on local property taxes. Increased federal and state investment is crucial to ensure adequate resources for all students.

- Improving Higher Education Affordability and Access: This includes significantly increasing need-based grant aid, such as “doubling the Pell Grant,” to restore its historical purchasing power and reduce student debt. Strategies to control tuition growth, like state-level tuition caps, are also necessary.

- Addressing the Student Loan Burden: Multi-pronged strategies are needed, including expanding and simplifying income-driven repayment plans and strengthening programs like Public Service Loan Forgiveness. Targeted loan forgiveness and re-evaluating loan limits can also mitigate future debt accumulation.

- Sustained Public Investment: Recognizing education’s indispensable role in national productivity and innovation necessitates sustained public investment across all levels of the educational system, including robust funding for research and development.

VI. Conclusion

The fiscal foundation of U.S. education is a critical determinant of the nation’s economic vitality and social equity. Systemic financial challenges—from K-12 funding disparities rooted in wealth inequality to the escalating costs and debt burden of higher education—threaten to undermine its foundational role. By implementing strategic policy reforms that prioritize equitable funding, control costs, and alleviate debt burdens, the United States can strengthen its educational infrastructure. This investment is not merely an expenditure; it is a critical commitment to fostering a more prosperous, innovative, and just future for all its citizens.